I heard the yearning again. The voice was clear, insistent, and undiminished: you must go to The Broad museum, the yearning told me, to see the paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat. A few days later, I obeyed, and hopped in the car.

For the past year or so, I’ve been hearing from the yearning every few months, telling me to go to The Broad and spend quality time with Basquiat’s works. It hits me when I’m buying milk at the supermarket or driving to the gym and jogging late at night after a long day of work. There’s no way to predict when the yearning will speak.

Before all that, I had spent nearly two years working on a short book about Basquiat, the world-renowned American artist who died in 1988. I first published it as a long essay at Letters From Over Here’s previous home on Medium, and I expect a publisher to swoop it up soon. Titled “A Visit with Jean-Michel Basquiat on His Birthday,” it takes down three, big-time critics that bullied Basquiat in the 1980s while also laying out, point by point, how he was creating meaty, world-changing art.

After spending countless hours on that project, my mind-spirit, now and then, still wants a dose of Basquiat’s paintings. That’s why I hear from the yearning. So on a recent afternoon, I took a 35-minute drive to The Broad in Downtown Los Angeles — the museum has two viewing areas filled with only Basquiats.

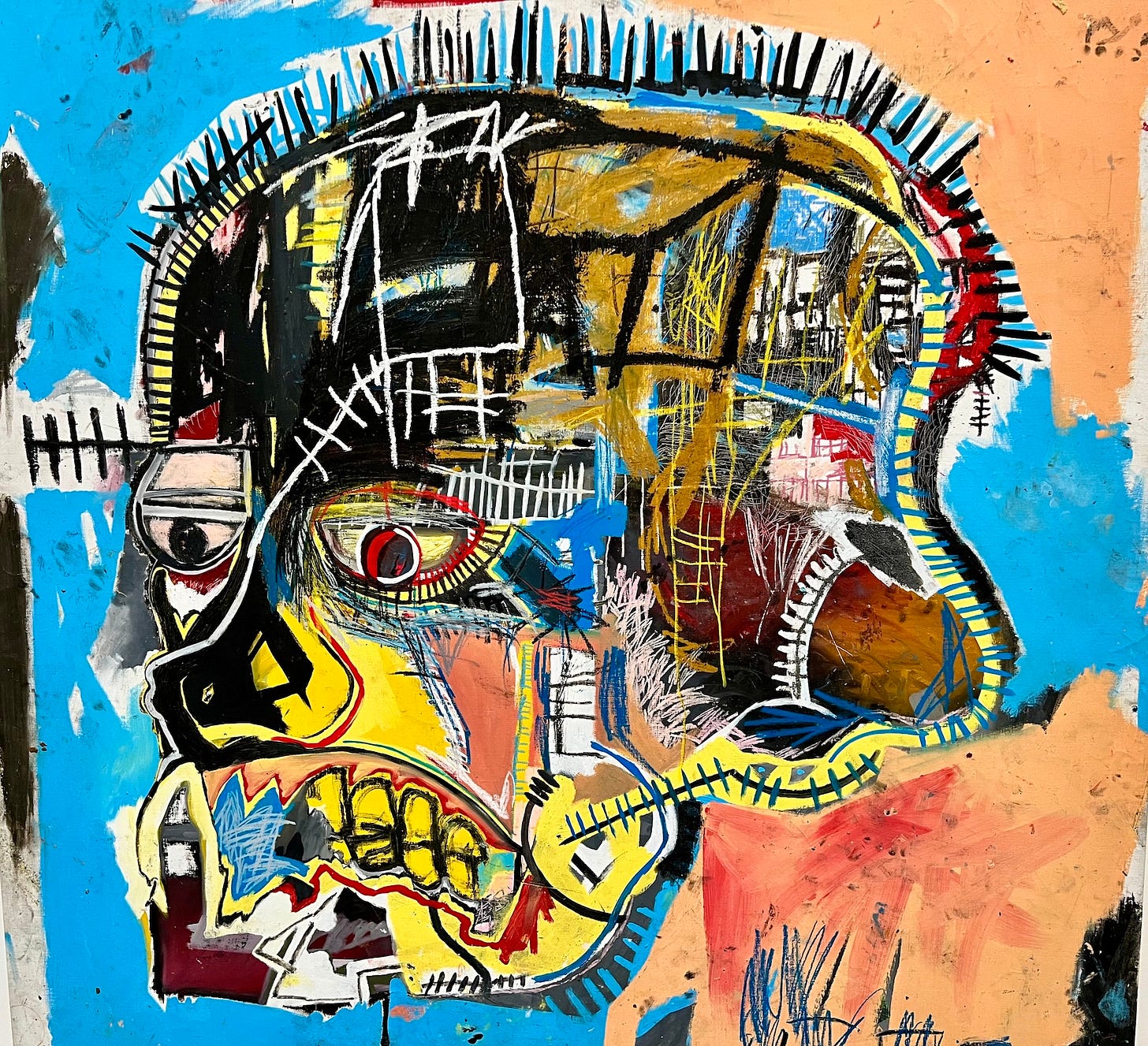

I had a mission for this visit. I wanted to focus on how Basquiat used eyes to set a tone in a painting – and to give it a power that never fades away, even thirty-six years after his death. When I walked into the first viewing area, at The Broad, I immediately saw Untitled from 1981. The painting depicts a large, frazzled skull, with scratched up windows in the rear of the skull. (Windows into the mind?)

Some people think it’s a self-portrait. If so, Basquiat, who was twenty or twenty-one when he created Untitled, may have already been feeling the pressures of needing to turn out one fantastic painting after another so early in his career – a career that would soon skyrocket into international superstardom. It’s the eyes that exude that weighty vibe.

I’ve studied Untitled, over the past three years, for hours. The eyes appear to be looking down, and, for me, come across as confused, life-burdened, and even a bit forlorn. In one eye, the pupil has some red in it, and the eye is framed in red. The other eye has nothing – just a black pupil, looking somewhat dead. Around the eyes are scars and scratches. If Basquiat did nothing with those eyes, the painting wouldn’t have packed the same disturbed wallop.

When I’ve brought friends to The Broad, and mentioned the eyes, they’ve always been surprised. They could feel the power of the work, but didn’t understand where it was coming from or what was causing it. When I told them to look at the eyes, they got it — instantly. Then they wanted to look at the eyes of the other paintings.

Such as Horn Players from 1983. For a triptych, Basquiat painted portraits of two of his favorite jazz musicians: Charlie “Bird” Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. Parker, in the left panel, is blowing into his saxophone, with Basquiat painting squiggly lines and musical notes coming out of it. Parker’s eyes stare straight ahead, looking relaxed, as if he’s in a kind of trance as he plays his music. In another panel, Basquiat paints Gillespie’s eyes with small pupils and lots of white, framing them with a pair of glasses. It looks as if his eyes are wide open, suggesting that he’s surprised or blown away by what Parker is playing.

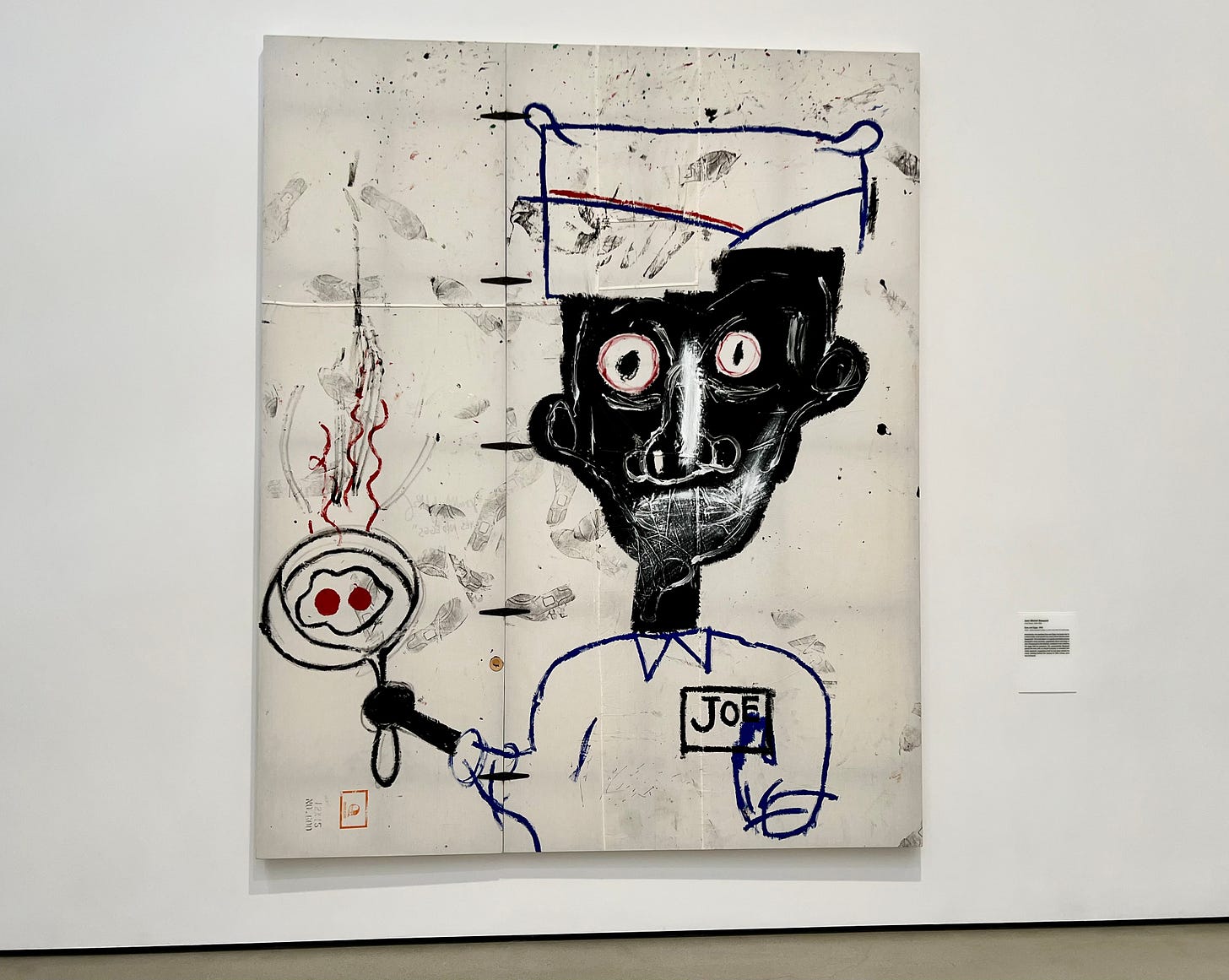

Another painting is the massive, 1983 portrait of a short-order cook, titled, fittingly, Eyes and Eggs. The figure is a Black man, with a name tag of “Joe,” frying eggs in a skillet. Joe’s eyes are large and ringed in red and stare straight ahead, but with a look of bewilderment — and a kind of unspoken plea for help. That’s what strikes me about the eyes, anyway. One thing’s for certain: they’re not the eyes of someone who’s happy.

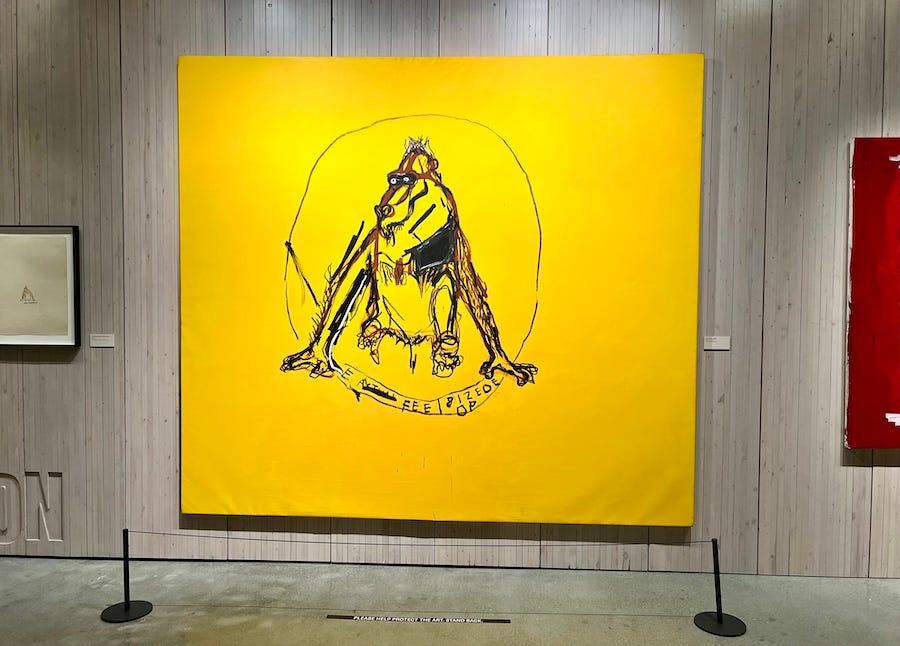

I first noticed Basquiat’s use of eyes, in 2023, at the Jean-Michel Basquiat: King Pleasure exhibit in Los Angeles, which was set up across the street from The Broad. I went there nearly a dozen times to do research for my book, and, every time, I was drawn to a painting titled Dry Cell from 1988. It’s another giant work, depicting a large West African baboon known as a mandrill.

I wasn’t sure why the painting always grabbed me, but after four or five visits, I realized it was the eyes, beaming a kind of pride and stateliness. Basquiat, in other words, had captured the mandrill’s spirit – no easy thing to do, and a beautiful idea on Jean-Michel’s part.

A bit later, I knew I was onto something about the eyes when I found a video of Michael Patterson, who was the subject of a portrait by Basquiat. The painting was done in 1985, and it came up for auction at Christie’s in 2020. That’s what the video was made for.

We watch Patterson walk into a room and up to the painting, mesmerized by what Basquiat had created. At one point, Michael says, “Once he captured the eyes, that’s when I kind of freaked out. He captured my soul in my eyes.” Aha! I thought. It’s the eyes!

At The Broad, twelve Basquiat paintings were on display, and all of them featured the power-making eyes. The museum’s Basquiat collection is considered one of the best in the world, with the paintings probably going for tens of millions of dollars if they’re ever sold. It’s all about the eyes.

Tellingly, the big-time critics that attacked Basquiat, as far as I know, never wrote a word about the eyes. Instead, they were more interested, even obsessed, in tearing Jean-Michel apart. It didn't work. Those critics are now dead, and Basquiat’s paintings have only grown more popular, and the eyes only more powerful. Look at the eyes. Always look at the eyes.